This post is the fourth and final close reading of “In Conclusion: A Four-Part Series on Epilogues and Endings in Queer Love Stories.” Before you read any of the posts on specific books, I’d recommend having a look at the introduction to the series first. Part 1 analyzes Something Spectacular by Alexis Hall, Part 2 Even Though I Knew The End by C. L. Polk, and Part 3 We Could Be So Good by Cat Sebastian- I’d only recommend reading those if you’ve already read the books. Happy reading!

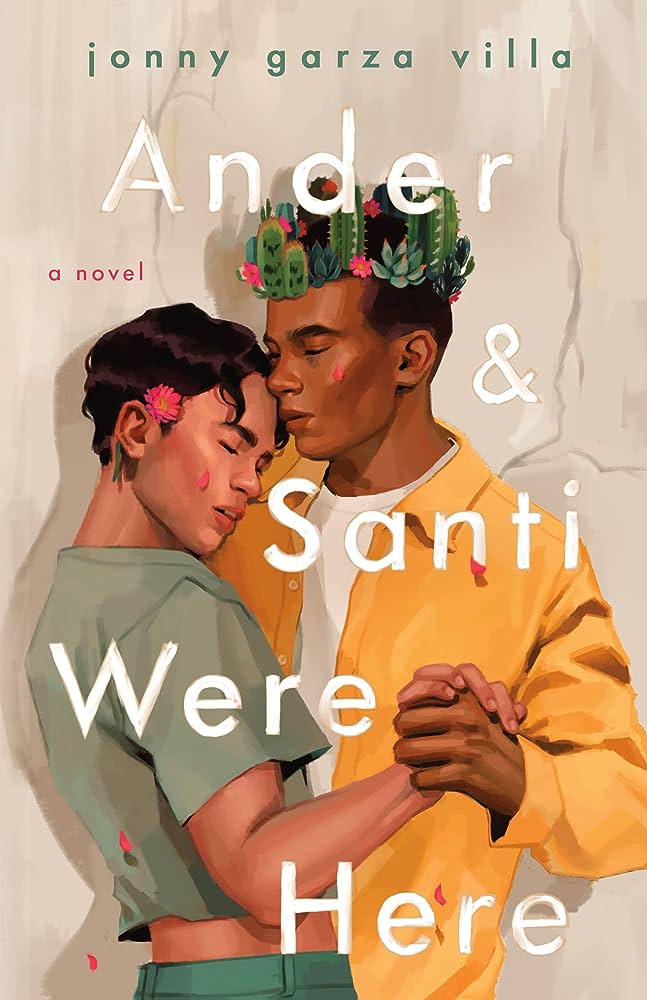

Ander & Santi Were Here is a recently-published YA romance novel that has left an incredible impression on me. It tells the love story of Ander – a talented muralist who is about to head off to their first year of art college – and Santi – a new employee at their family’s restaurant. It starts as a sweet, summery teen romance, which quickly develops much more serious stakes as Ander learns that Santi is undocumented and living under threat of deportation. The journey that Ander and Santi take, standing up for the rights of undocumented people and carving out a space for their own love, is one of the most memorable stories I’ve encountered in this genre in a long time. It also offers a fascinating chance to look at the politics of queer utopias. Here’s the cover and blurb:

The Santos Vista neighborhood of San Antonio, Texas, is all Ander Lopez has ever known. The smell of pan dulce. The mixture of Spanish and English filling the streets. And, especially their job at their family’s taquería. It’s the place that has inspired Ander as a muralist, and, as they get ready to leave for art school, it’s all of these things that give them hesitancy. That give them the thought, are they ready to leave it all behind?

To keep Ander from becoming complacent during their gap year, their family “fires” them so they can transition from restaurant life to focusing on their murals and prepare for college. That is, until they meet Santiago Garcia, the hot new waiter. Falling for each other becomes as natural as breathing. Through Santi’s eyes, Ander starts to understand who they are and want to be as an artist, and Ander becomes Santi’s first steps toward making Santos Vista and the United States feel like home.

Until ICE agents come for Santi, and Ander realizes how fragile that sense of home is. How love can only hold on so long when the whole world is against them. And when, eventually, the world starts to win.

Cover image and blurb from the author’s website. CW at Leigh’s review here.

This novel sets itself a fairly thorny issue for its denouement: how to end the love story on romance’s required hopeful note, without giving readers the false impression that the threat of unjust deportation is one that can be easily avoided. Part of the praxis of this novel’s conclusion is that it has to be hard-won, has to involve a sacrifice that attests to the ongoing injustice of US immigration policy. Garza Villa accomplishes this by having Ander decide to give up their plans for art school (already shown to be a place where institutional investment in whiteness would have been hostile to them as a person and as an artist), leave their family behind in Texas, and move to Mexico to start a new life with Santi. The epilogue starts with the three words “My Mexican Heaven,” and describes the peace and joy of the couple’s life together. Here’s the very last passage:

Falling asleep with Santi resting on me. A small pool of drool forming on my chest. My hand slowly rubbing his head. A bedroom made even more stuffy from everything we’ve spent the past hour doing. Knowing that tomorrow we get to do this all over again.

Having all the time in the world. And peace. And happiness. And rest. And knowing that we are here, we have each other, and no one can take that from us now.

No one can take him from me now.

Mi querido.

Mi Santiago.

The epilogue is linguistically fascinating, in that the entire chapter consists of a series of sentence fragments relating back to the phrase “My Mexican Heaven.” The concept of “Mexican Heaven” is introduced early on in the book, both as a reference to a poem by José Olivarez and to a mural that Ander has painted inspired by it. Yet while the epilogue opens on a nod to previously-established references, readers get the sense that the final chapter takes place in a different world, in a different time, and on a different plane from the rest of the narrative. To begin with, the italicized emphasis on “My Mexican Heaven” marks its difference from Olivarez’s poem and Ander’s painting. There’s also a grammatical rupture at the heart of the epilogue, as the reader is left to infer the verb that connects “My Mexican Heaven” to the rest of the text. It reads

My Mexican Heaven.

Waking up to Santi’s lips going from my forehead down to my nose…

Rather than

“My Mexican Heaven [is] waking up to Santi’s lips going from my forehead down to my nose.”

The missing coupla of the “to-be” verb results in a sense of separation – but rather than a pessimistic feeling of breakage, the poetry of the images and the cadence of the language turn that separation into something different. To me, the rupture of the epilogue feels like a space for evolution. It is the gap across which Ander turns the present into the past, and the future into heaven- into a utopia.

To conclude with the two protagonists living in their own utopia felt weighted with political significance, particularly for a novel in which two young, queer characters faced the brutal realities of 21st century US immigration policy. One of the main other texts I read when I was trying to come to grips with what it meant to conclude this story with a utopian HEA was José Esteban Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia. He argues that “the future is queerness’s domain” (1), and that utopia is thus a central concept in queer theory. Muñoz sees utopia not as naïve escapism, but as a vital political act. In the face of a “here and now” that “naturalizes cultural logics such as capitalism and heteronormativity” (12), utopia is a powerful – and deeply queer – way to imagine something different.

Thinking about the queerness of utopian imagining – thinking beyond what is normativizied in the “here and now” (Muñoz 12) – also helped me contextualize one of the most striking features of this book’s ending. In leaving their family, Ander also leaves a community where their queerness is both recognized and celebrated. This recognition and celebration comes across in dozens of ways in the text, but the language is one of them: all of Ander’s family members and friends use the correct pronouns and linguistic forms for them in English and Spanish without needing explanation or correction. Neither Ander nor Santi are made to feel unsafe because of their queerness. The sole plot threat to the main couple’s love story comes from ICE and the risk that Santi will be deported.

This effortless acceptance might tempt one to suggest that queerness is not “an issue” in the novel, but I don’t think that’s quite fair. While it is neither a source of trauma nor of conflict, never stigmatized or remarked on by “outsiders,” queerness is nonetheless fundamental to the entire narrative, including the ending. Readers can see how important Ander’s sexuality and gender identity are to their sense of self, and we can hear that sense of self affirmed every time another character speaks to them. But queerness is also, I would argue, central to the structure of the text. Ander and Santi navigate a narrative in a shape that is immediately recognizable to queer readers – particularly, though this is a contemporary work, recognizable to readers of queer historical romance. It shows how two protagonists living in a political environment hostile to their personhood and survival find a space in which to live out their love.

The fact that the political hostility that the text highlights and put in front of the reader is the hostility towards undocumented persons living in the United States, does not negate the fact that “Mexican Heaven” is also a celebration of queer love. Rather, the text directs the reader to think about the way the two forms of safety reinforce each other : the utopia that the text constructs for Ander and Santi must see them as whole people, and care for them at the intersection of all their identities. The language of the final passage confirms that queerness is a central element of that intersectional care. Through both allusion and physical representation, the reader is reminded that the heaven Ander and Santi find is one in which they can share love, share bodily contact, share a bed, and share a future: Falling asleep with Santi resting on me. My hand slowly rubbing his head.

Right at the center of this final passage is an evocation of time:

“Knowing that tomorrow we get to do this all over again. Having all the time in the world.”

Ander’s “Mexican Heaven” is a vision of futurity – a space from which they can project themself into the future. Looking back at Muñoz’s theorization that imagining alternative futures is, itself, fundamentally queer, we can see how that Ander and Santi’s utopia makes queerness central to how both characters live their fullest, most joyful lives. More broadly, I think it reminds readers of the importance of celebrating intersectionality at the heart of queer utopia. It’s a book I cannot recommend highly enough.