I’m back with Part 2 of “In Conclusion: A Four-Part Series on Epilogues and Endings in Queer Love Stories.” Before reading any of the individual close readings, I’d recommend checking out the introduction to the series here first. Part 1, on Something Spectacular by Alexis Hall, can be found here. Happy reading!

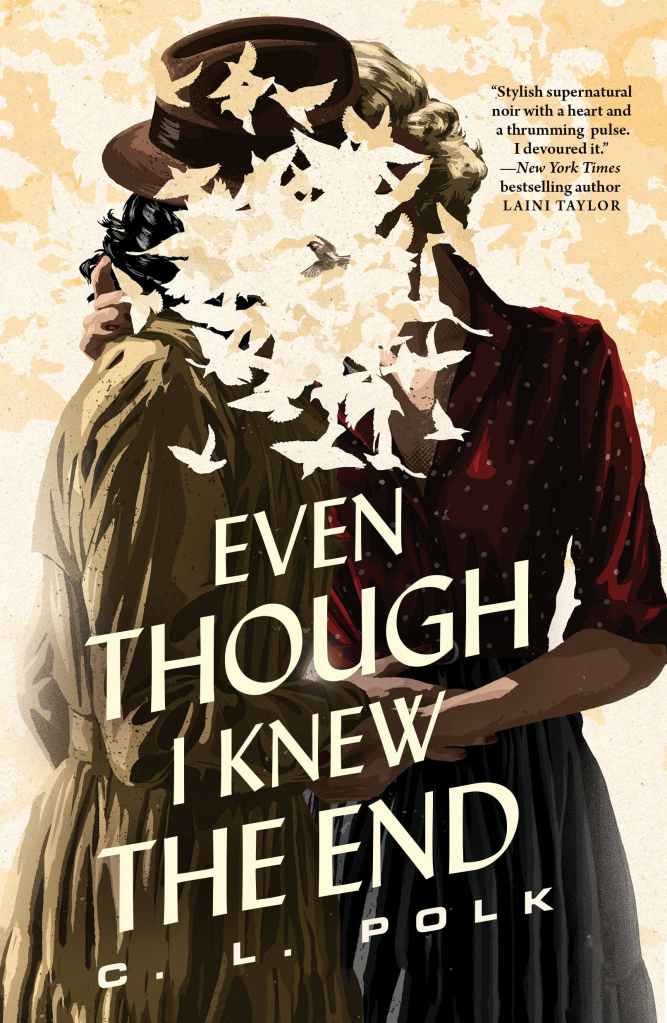

Even given that my corpus for this blog post series aims explicitly for eclecticism, the inclusion of Even Though I Knew The End probably merits some further discussion. It’s not marketed as a genre romance, and so unlike the three other books I’m looking at, there isn’t actually a promise of any kind of “traditional” HEA. It’s also set in the past, but in a fantasy version of the past with angels and demons and magic, and so some of the theoretical discussion about historicity doesn’t apply here. Still, I think this book warrants inclusion because it’s intimately engaged with the intersections between queer pasts and futures, and how the constraints of the past have their place in discussions of happy endings.

A magical detective dives into the affairs of Chicago’s divine monsters to secure a future with the love of her life. This sapphic period piece will dazzle anyone looking for mystery, intrigue, romance, magic, or all of the above.

An exiled augur whose soul is due for Hell on Monday is offered one last job before serving an eternity in hell. When she turns it down, her client sweetens the pot by offering up the one payment she can’t resist―the chance to have a future where she grows old with the woman she loves.

To succeed, she is given three days to track down the White City Vampire, Chicago’s most notorious serial killer. If she fails, only hell and heartbreak await.

Cover image and blurb from the author’s website. CWs available in Emmalita’s review here.

In reading this book, I thought a lot about how it operates in a world of layered and interrelated constraints: the constraints of time, the constraints of religion, and the constraints of homophobia. The most evident of these is time. We learn quite early-on in the book that Helen has sold her soul to a demon to save her brother’s life, and is going to die soon because of it. While she briefly escapes this constraint, it returns as Helen sacrifices her soul to have 10 more years with Edith, the woman she loves. There’s a sense of perpetuity to this time constraint, one that collapses the beginning and ending of the narrative, bringing the past and present closer together in ways that will echo thematically through the book.

The constraint of religion is a more unstable presence. There’s actually not much in the way of “organized” religion here, although churches and priests and prayers are mentioned. It’s more present in the fact that demons are real, as is the magic used to fight them. It’s also a pervasive presence in the habits and speech of the characters, which comes through in several arresting bits of prose: a face that moves through the “stations” of a reaction like stations of a cross, a clock that brings its hands together at midnight like “prayers.” Religion is both a threat and a tool to fight back against it, but its pervasiveness even into the language of the text cannot help, I think, but evoke for the modern reader the more concrete way that organized religion has, throughout history, constrained the lives of many on the margins, even as it proves a spiritual resource for others.

That homophobia exists as a constraint on this world is mostly evident through the haunting traces it leaves on the text. We see homophobia in figures and images that feel absent or ghostly: the almost-empty building that Edith and Helen live in away from judging eyes; the past of the hidden queer bar that they drink in; the way the bar itself is hidden behind passwords and door guards; most horridly, the women in the Dunning Asylum, hidden in among the demonically possessed, being subjected to conversion therapy.

Even Though I Knew The End is structured by various combinations of these three constraints – time, religion, homophobia. But it also shows us how, even though these constraints produce ghosts, they also leave space for joy. That’s especially clear in the final passage, where Helen realizes she’s going to have to cohabitate with her own ghost: the knowledge that she only has ten years to spend with Edith.

Ten years. It wasn’t enough time, but I would live every blessed second of it. “We’re going to San Francisco.”

She smiled up at me. “We’ll get a house in North Beach.”

“Right away.” I said. “I’ve got the down payment and then some.”

She sighed and pulled me close. “We’re going to be so happy.”

We would be. I’d dust the knickknacks, burn the sausage, wake up next to her every morning. I’d be grateful, even though I knew the end.

There are two types of time in this passage, both of them occurring as couples: present/future, and past/conditional. When Helen and Edith talk to each other, they use the present tense to describe their current circumstances (“I’ve got the down payment”) and the future to talk about what’s to come (“We’re going to be so happy/We’ll get a house”). In Helen’s interior monologue, the primary tense is the past (“She smiled up at me”) and to talk about the future she uses the conditional (“I’d dust the knickknacks”/“I’d be grateful”), though it’s somewhat disguised by the contraction of “I would” into “I’d.”

In English, as in many languages, grammatical rules dictate that when narrating in the past tense, we use conditional conjugations (“I would”/“I’d”) this way, to talk about the future. Which, when you think about it, is… not exactly intuitive? I associate the conditional with uncertainty. In everyday speech, it’s mostly used for counterfactual hypotheticals (“If I won the lottery, I would buy even more books”), a chain of events that is at best uncertain, if not impossible. But the past tense, conversely, I think of as the tense of certainty. It’s the narration done by someone who has already reached the end of the story, who “knows the end” without internal ambiguity, and has decided how to tell it. The conditional within past narration has a bit of a ghostly function, a grammatical revenant that haunts the certain past with uncertainty about the future.

And it’s used to beautiful effect here, alongside the much more optimistic combination of tenses that Helen and Edith use to talk to each other about their lives to come. On the one hand, the present and the optimistic future, with the confident linearity of the HEA; and on the other, the past, already destabilized by the uncertainty of the barely-disguised “I’d” conditional. Optimism, even when you know the end, and the end is going to hurt.

That cohabitation of joy and pain, right up until the end, also helps, I think, to process the harshness of some of the constraints that characters live under in this book. As I wrote this piece, I was thinking a lot about something I was reading concurrently, a bit of academic literary theory recommended to me (by a very smart friend) called Feeling Backward by Heather Love. It’s a book that was challenging to read because its main thesis is somewhat antithetical to me as a queer romance reader. Love insists on the importance of looking back at texts from the past that dwell on feelings of queer shame, or failure, or loss, considering them not just as things to move beyond, but as something to sit with and remember. To preserve, even, from a risk of effacement that comes with increased mainstreaming of queer identities. She also invites readers to recognize these feelings’ persistence, even into a more accepting present:

“It may in fact seem shaming to hold onto an identity that cannot be uncoupled from violence, suffering, and loss. I insist on the importance of clinging to ruined identities and to histories of injury. Resisting the call to gay normalization means refusing to write off the most vulnerable, the least presentable, and all the dead” (30).

Love’s analysis is way more complex than I’ll be able to do justice to : a really sharp reading here points out that she’s neither dismissing optimism nor fetishizing marginality. And while ultimately I am still more drawn to the optimistic queer joy on offer in the endings of genre romance, Love’s work made me think about how to take in an ending like Even Though I Knew The End. A story of queer love that is explicitly haunted by ghosts – ghosts that maybe aren’t really dead – of homophobia and oppression. A “happy for now” ending that is desperately hopeful as it cohabitates – thematically, grammatically – with uncertainty and loss. I think what’s the most powerful is that despite all of the constraints that structure the novel, the two main characters end up living beside those constraints rather than being crushed under them. The entire theme of bodily possession and cohabitation with angels and demons and sprits gets turned into something that is, on some level, about queer experiences of time. And I loved seeing how this book used grammatical tools to infuse that interpretation into the prose as well as the structure of the novel.