Hello! Its been a while since I wrote – almost a year, to be exact, and in that time, I’ve been thinking a lot about what I want to do with this blog. I’m still reading romance, but I’ve also been branching out into other genres that live nearby, and some of those books are what I’ve most been longing to write about. But, you know, it says “Close Reading Romance” on the masthead of this thing, and I wasn’t sure exactly how that would fit. Or, for that matter, what to do with my desire to also write some pieces that focus less on prose, and more on Big Genre Musings like “What does it mean to read for pleasure?” and “What is ‘no plot, only vibes’ doing for readers?” and “What’s happening when we say some books with HEAs still aren’t romances?” And then, as a very smart friend reminded me, this is my blog and I can do what I want! So, I’m not going to stop doing close readings. And I’m definitely not going to stop writing about romance. But I might use this space to do some other things too, and today’s post is (sort of) one of those other things.

Basically, the two recent reads that I most want to press into the hands of everyone I know with a wild look in my eye… are not genre romances. But I came away feeling like they each had, in their way, the soul of a genre romance. Or, at least, that they rewarded a reading that searched for that soul. The books in question are Siren Queen by Nghi Vo, and The New Life by Tom Crewe. I want to tell you about those books – and without spoiling too much, about why you might want to pick them up if you’re a romance reader – and then talk about why I’m increasingly skeptical about strict divisions between genres. So, without further ado, a little bit about the best two books I’ve read so far this year, and how their writing makes them tick.

Siren Queen by Nghi Vo

More info on Siren Queen here.

My short pitch for Nghi Vo’s Siren Queen is that if you’re a reader who doesn’t love complicated and strange world-building, this book could change your mind. Gorgeous prose and masterful story-telling help readers experience the power and sometimes horrible beauty of this fantasy world without needing to fully understand its rules: it’s the difference between experiencing a new country by visiting it and tasting all its sensory delights, and taking a pop quiz on its history. The first sentences of the book ask the reader to follow the narrator into the unknown:

Wolfe Studios released a tarot deck’s worth of stories about me over the years. One of the very first still has legs in the archivist’s halls, or at least people tell me they see it there, scuttling between the yellowing stacks of tabloids and the ancient silver film that has been enchanted not to burn.

In that first story, I’m a leggy fourteen, sitting on the curb in front of my father’s laundry on Hungarian Hill.

This passage suggests a certain fluidity between what is and isn’t real. My instinct is to read the second sentence as starting with a metaphor (stories that “have legs” and “scuttle” around tabloids) and moving to a literal description of a fantasy-genre world (film that has been “enchanted not to burn”). However, the narrator, for all intents and purposes, treats these two elements as equally real. Nothing is over-explained: the “tarot deck’s” worth of stories is also a disorienting image, as tarot isn’t commonly understood to be read for stories so much as for information about the future.

The difference between metaphor and reality, between reading for story and reading for future understanding, is all the tension of this book. It’s the story of Luli Wei, an actress in a version of old Hollywood where magic is real, and so are monsters, and where becoming a “star” is both Luli’s cinematic goal and a literal thing that happens to immortal Hollywood actors. Because this story thrives on the liminal spaces of uncertainty – you never learn the backstory of a number of the fantastical elements of this narrative – the moments where the narrator offers reassurance to readers are all the more meaningful. She does so at the end of the above passage, for example, by telling readers that the story of her fourteen year old self is “bullshit, of course.” Luli has the real story, a key element to building narrative trust. There’s one other major thing that Siren Queen structurally reassures the reader about. This, from page 20:

Even with it all, the money, the crackling atmosphere of the set, the kiss Maya Vos Santé had given me, I might never have longed for a star of my own and a place high in the Los Angeles sky. I don’t know what else might have happened to me; I was too young when it all began, and I hadn’t shown the twists and hooks that would have drawn other fates to me.

(“Oh, you were always meant to be in movies,” Jane said. “One way or another, you would have found your way in, no matter what was standing in your way.”

“Is that a compliment?” I asked her.

“It’s better than a compliment, it’s the truth.”)

Interspersed throughout the novel are these parenthetical asides between Luli and a woman named Jane, clearly a romantic partner. Luli loves a number of women throughout the story – the mercurial and beautiful actress Emmaline, and a firecracker of a screenwriter named Tara – and while neither of these women end the story in a romantic relationship with Luli, they are integral to her story. Jane only appears in these asides, and a particularly emotional mention in the epilogue.

The presence of each of these love stories is probably enough to appeal to the romance reader: they’re each compelling and gorgeously-written. But the inclusion of the Jane asides, for me, goes beyond the simple presence of a love story that ends happily. By making it clear that Luli is telling this story to a lover, Siren Queen emphasizes the value of allowing readers to start a story already knowing that love survives- a fact that particularly stands out when so little else is fully known and understood. This is particularly important when it comes to queer love stories in the kind of hostile outside world in which Siren Queen is set. Luli lives in a universe where her love affairs with women have to be kept from predatory and prejudiced studio executives. They are never, however, kept from the eye of the reader. Whether it’s the sparks of Luli’s first meeting with Tara, the beautifully rendered sex scenes with Emmaline, or (especially) the HEA-infused asides with Jane, the importance of queer love is one of the most concrete things in this confusing world. Without necessarily being a romance, this book has a lot to say about the value of a love story that is more legible to the reader, right from the start, than the magic, the history, the monsters, and the stars of the universe.

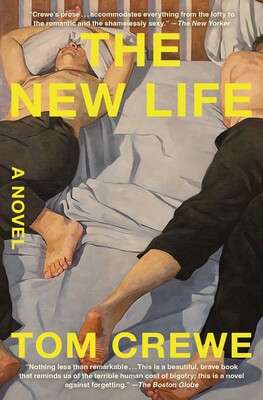

The New Life by Tom Crewe

More info on The New Life here.

The question of what is said and what isn’t also makes for an interesting romance-informed reading of The New Life by Tom Crewe. Like in Siren Queen, there is a clear love story between two characters which ends optimistically: in this case, it’s between John Addington, one of two men in 1890s England writing a controversial book in defense of homosexuality, and his lover Frank. But it’s the second main character of the story, John’s writing partner Henry, who ended up being one of the most fascinating characters in my recent reading memory. Henry is incredibly opaque to himself and to the reader, especially when it comes to desire. He is married to Edith, but they do not have a sexual relationship: Edith has a lover named Angelica, and the contours of what Henry wants from his marriage – or from outside of it – aren’t always clear to himself or to others. Yet together with John, he is preparing to take on the risk of publishing a book arguing for the decriminalization of homosexuality, right as the Oscar Wilde trial is gripping the nation.

Part of Henry’s opacity comes from how he’s constructed through the novel’s prose, as in this passage where he is about to interview his friend Jack, as part of a set of anonymized oral histories of gay men collected via survey for his book.

He was not made by Jack to feel like an oddity, as though what feelings he had were irredeemably childish and virginal for not being roughly expressed. He never wondered about Jack’s quietness. He was not then in the habit of thinking about other people. It was not that he didn’t care – with the exception of Edith, he had never cared for anyone so much as he did for Jack at that time – only that he saw other people purely as they presented themselves to him, as if he were a backcloth receiving a projection and this was his sole purpose, to show them to themselves.

The writing of this novel has, at times, an incredible restraint to it. If Siren Queen offered an opulent surfeit of things said without needing to be fully understood, The New Life is all about what is not said, yet which still demands understanding. Henry’s interpretation of himself as a “backcloth receiving a projection” is echoed in the prose, which suppresses active agency in favor of more circumspect or passive-voiced formulas (“he was not made by Jack to feel”/“as they presented themselves to him”). In a passage that directly follows this one, Henry’s wife Edith chastises him for not asking about his best friend’s love life in the course of their interview:

She bent her head back, squeezing her eyes shut. “You realize you didn’t ask, whether he has someone.”

“That is not one of the questions.”

“I know.”

“Should I have done?”

“Oh, Henry,” she said. “Yes, you should.”

For one of the most moving passages of the novel, the prose is spare, stripped even of dialog tags except where necessary. The chapter ends abruptly after these lines, and the reader is left with the work of understanding why Henry has not asked his friend about a partner, what it would have meant to Jack to be asked, and why that’s something Edith can understand, but not her husband.

What I found the most fascinating about Henry is that as a romance reader, I kept trying to classify him in terms of his desire. Was he straight, queer, an “ally,” someone who didn’t know what he wanted in a sexual partner, who preferred non-sexual intimacy, who preferred self-pleasure over partnered sex? By the end of my reading, I might have said that none of these things were true, or that many of them were a little true, along with other unexpected truths. But what most struck me, as I read, was realizing how much romance has trained me to read character through desire. Encountering a character who resisted that reading was intriguing, both in terms of narrative arc and prose. Yet at the same time, Henry is surrounded by legible romantic desire- his wife’s desire for her lover Angelica, his writing partner’s desire for Frank – and it is his proximity to, and examination of, those forms of romance that eventually helps him understand his own relationship to desire (slightly) more clearly.

Coming to a deeper understanding of oneself by encountering narratives and impressions of others’ desire perhaps probably resonates with how a lot of us feel as we read romance: in some ways Henry resists a romance reading while also performing one on those around him. Which is an interpretation of this book that wouldn’t have been available to me if I wasn’t coming to it with my specific genre lens. The New Life contains both a distance and a proximity to romance that are in constant tension- and much like the “backcloth” that Henry evokes in the first passage above, a knowledge of genre romance reflected The New Life back to me a little differently than it might to other readers.

What’s in a genre?

It occurred to me, while writing about these books, that a shorthand I might use to tell romance readers that they would enjoy Siren Queen and The New Life would be: “they’re not romances- they have love stories that end optimistically, but there isn’t a central focus on one love story.” And for these two books, that’s a) very true and b) not necessarily news to anyone who picks them up. Both books are being marketed in other genres that fit them better (and, not to open a giant can of worms, but at least in the case of The New Life, genres that have drastically more cultural cachet than romance). But… at the same time, what happens to other books that we say this about? Books that are being marketed, and received by some readers but not by others, as romance? Because “it ends happily but I didn’t feel like the love story was the central focus” is a way I’ve seen many books discounted from the genre: often, not coincidentally, when they feature MCs who are marginalized and whose personal growth arcs (alongside their love stories) are making important interventions in the genre. Placing a book inside or outside a genre produces meaning : it can set expectations, empower readers to find what they want, and situate a book in a wide literary universe. But it can also bring in biases that have little to do with narrative codes. If we’re skeptical towards claims that a personal growth narrative is “litfic” if it’s written by a man and “women’s fiction” if it’s written by a woman (just to cite one broadly-sketched example), it might also be worth a helping of skepticism towards claims that there’s a quantifiable amount of focus on an individual character’s growth, or depiction of personal hardship, or a particular relationship shape that automatically disqualifies a book from being read as a romance.

Which isn’t to say that I think we shouldn’t be having those conversations as readers! On the contrary, I think a more flexible understanding – not necessarily even of “genre romance” but of “genre” itself – would leave a LOT more room for reader interpretation and agency. In the course of doing some reading for my day job, I came across a definition of genre that felt more promising to me in this regard. I first encountered it in this book (though it appears to come to Rieder via Paul Kincaid), and it suggests that we can think of a genre as “a group of objects that bear a ‘family resemblance’ to one another rather than sharing some set of essential, defining characteristics.” This appealed to me quite a lot. What if, instead of talking about books having a binary “in or out” relationship to a genre, we were able to talk about how much family resemblance they bore to other books we love? It may be a bit slipperier, because signs of “family resemblance” are varied enough that they can’t be exhaustively enumerated or defined ahead of time. But that slipperiness also means that I, as the reader, have to look for those signs of resemblance as I read: to seek out the early reassurance of an HEA in Siren Queen and the use of desire to create character in The New Life. And then I get to talk about what I found, creating an understanding of genre that’s collaborative, open, done from the ground up. So while I’m not necessarily advocating that we dissipate the definition of a genre beyond functionality (I’m not advocating anything, really, I still want to be able to find my HEAs!) I do think that the idea of a search for family resemblance executes a shift from reading “genre romance” to reading “as a genre romance reader.” Which, at least in the case of Siren Queen and The New Life, actively enriched my experience of both books.

Anyway, I hope that, if nothing else, these ramblings encourage you to pick up one or both of these books. And, if you’re so inclined, I’d love to hear recommendations in the comments for other books you think can be read more richly with a romance genre lens.

Discover more from Close Reading Romance

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I want to go read these immediately and then come back and discuss!! This was great

LikeLike

Aaaa thank you so much for reading! I hope you love the books -and come back to discuss – if you pick them up. Siren Queen blew my tiny mind, and I’m suspicious that The New Life is going to end up being one of – if not THE – best read of my year.

LikeLike

I started A New Life but got distracted. I will return to it, with your recommendation in mind.

In answer to your request for books that aren’t technically romance but can be approached as such: In Memoriam by Alice Winn. The story of two young men, set against the backdrop of the First World War. A gorgeous piece of writing but be warned, it is harsh, visceral and pulls no punches.

LikeLike

oh, In Memoriam is a great example – the ending truly surprised me (which is not something I can usually say as a romance reader)

LikeLike

I’m very happy to read anything you want to write here! Though as it happens, this is a topic I’m also interested in and I think that’s a really good framework for discussing those less easily assigned books (which are often all the better for it.)

LikeLike

Thank you so much for reading!

LikeLike

Pingback: July 2024 Wrap Up – The Smut Report