It’s time for part two of my three-part series on paratexts! Last week I wrote about “romance abstracts,” or the copy that summarizes the plot and introduces the characters. Today I’m examining everything that comes between the front cover and the start of the narrative: dedications, content warnings, epigraphs, and letters to the reader. While these pieces of front matter don’t have a unified or even necessary function (plenty of books exist without them), they still do a variety of preparatory work. Some provide context, some warnings; many evoke relationships to other novels or works of art. It’s also the home of the dedication, where a book ostensibly written for any and all readers proclaims itself to have been written “for” someone we don’t know. So I want to dig in to the kind of ownership model that dedications imagine: the ways that books that aren’t written for us become ours.

But first it’s time to back up a bit: how does front matter get us ready to read? Some front matter acts as an on-ramp to a literary world that moves at freeway speeds, and the author is just trying to make sure your tiny little vehicle doesn’t get crushed. The 2011 edition of Laura Kinsale’s For My Lady’s Heart begins with the following “Letter to my readers” explaining the book’s language use:

Dear Readers,

Many years ago, I read a medieval poem full of color and adventure about knights and mysterious ladies. It opened up an unknown world to me, a place of wild, dangerous forests and white castles, of mud and glorious spectacle; a time when blackbirds really were baked in pies. Against this rich background, I wrote a story about a powerful, devious woman desperate to reach refuge, and a knight—a true knight who never wavered once he swore his heart, a man who could not comprehend deceit.

To do justice to their world, I wove the music of their own medieval words into the dialogue. […] I was determined to make my characters’ words clear and understandable in the text, even though readers might never have come across them before. But I’ve also added a glossary so that you can be certain of their meanings if you have any doubt.

(She goes on to casually mention that the current ebook edition contains a condensed version of *the entire novel* in standard English, which is quite the digital extra).

The front matter then eases the reader into the language of the text: first with a poem from The Prologue of The Franklin’s Tale from The Canterbury Tales in standard English, and then the following epigraph:

Where werre and wrake and wonder

Bi sythes has wont therinne,

And oft bothe blysse and blunder

Ful skete has skyfted synne.

Where war and wrack and wonder

By sides have been therein,

And oft both bliss and blunder

Full swift have shifted since

Prologue

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

This pairing sets up where the language of the book falls – in the middle of the continuum between the original and its translation – and provides readers with a transition into the world of the novel.

In contrast to these “on ramps” that get readers into the world of the book, some front matter creates space around the reader to let the book in. Talia Hibbert’s Act Your Age, Eve Brown does this in several different ways. The Content Warnings are detailed, and emphasize giving readers tools to create an atmosphere of safety and care while they read.

This book mentions childhood neglect and anti-autistic ableism. If these topics are sensitive for you, please read with care. (And feel safe in the knowledge that joy triumphs in the end.) You should also know that, while writing this book, I elected to ignore the existence of COVID-19. I hope this book provides some form of escape.

“Eve’s Playlist,” which directly follows the content warnings, contains all the songs the heroine mentions listening to throughout the plot, allowing readers to bring some of the atmosphere of Eve’s world into their own while they read.

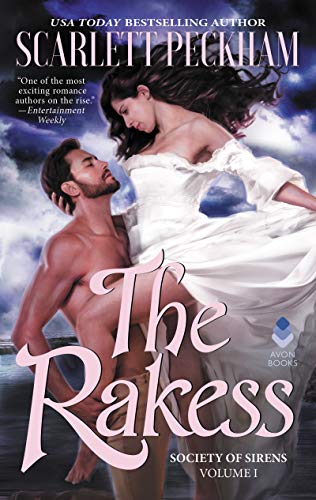

Front matter can also situate a book within literary traditions or periods of time. This function proves particularly salient for Scarlett Peckham’s The Rakess. The reverse-clinch cover might have suggested (and I think did suggest to some readers) a tongue-in-cheek playfulness with the rake trope, which doesn’t quite match the tone of the novel. The Content Warning page goes a long way to setting the record straight, informing readers that “while this is a romance novel, it is a dark and stormy one.”

Beyond clarifying the mood of the book, the front matter also situates the book’s approach to the idea of a “Rakess.” The dedication “in memory of Mary Wollstonecraft” puts the text into dialogue with feminist forebears, however I think the epigraph is the cleverest stroke of placing the book into historical context.

“Men, some to Business, some to pleasure take;

But ev’ry Woman is at heart a Rake”

– Alexander Pope

It would have been easy for The Rakess to trade on flippant novelty (“What if a rake, but a woman? How new and different!”) but I appreciate its refusal to abandon thinking about gender throughout history in favor of a “fun romp.” This epigraph reminds readers that the gendering of the Rake trope carries the weight of history behind it.

One of my favorite bits of time-bridging takes place in KJ Charles’ Slippery Creatures: both the “Reader Advisory” and dedication.

Reader Advisory

This book contains references to a pandemic and the spread of infectious disease.

For the essential workers keeping us going and for everyone who’s supporting them by staying home.

Slippery Creatures takes place in the 1920s and was published in 2020, though I don’t know at what point of its genesis the pandemic actually began. What matters more is that both the Reader Advisory and the dedication construct a bridge between the moment of the novel’s publication and the moment it depicts. This stands in contrast to most novels, where the only information that explicitly marks a historical romance with the moment of its writing is the date of publication. This front matter, intentionally or not, foregrounds a truth about all historical romances: they bear the imprint of the time they were written in – its conditions, its anxieties, its concept of what is right and wrong – alongside and interwoven with the time period depicted. Historical romance takes place, if not in the moment of its creation, then through it, and paratext is just one way that this relationship to the present of writing is affixed into the literary record.

Which brings me to what is often the very first element of front matter: the dedication. Originally dedications were a way of thanking patrons: quite literally announcing who the work was created for, in the commissioned-for-money sense. Dedications have since embraced a much broader meaning of a book being “for” someone, which is an idea I want to explore.

Take a look at a few different kinds of dedications, from the most general to the most specific.

For the readers. That Kind of Guy, Talia Hibbert

This kind of inclusive and general dedication has few variations, because there’s very little that all consumers of a novel share except being readers. It positions the book as being “for” anyone who picks it up and gets as far as the dedication page.

For everyone who’s ever been left. Untouchable, Talia Hibbert

For everyone doing battle. Invitation to the Blues, Roan Parrish

Dedications like this are almost as open-ended as the previous ones, as it’s hard to imagine someone who has never struggled or been left. They become more specific, however, as setups for the content of the books, which deal with getting over past relationships and struggling with mental illness, respectively. The dedications can also be interpreted as being for readers who have those particular experiences.

To everyone who’s ever doubted, as I did: Someone who looks like you can be desired. Someone who looks like you can be loved. Someone who looks like you can have a happy ending. I swear it. ❤ Spoiler Alert, Olivia Dade

For all the difficult heroines A Duke in Disguise, Cat Sebastian

For all the people who were told they couldn’t be princesses: you always were one. A Princess in Theory, Alyssa Cole

These are not unlike the previous category, but perhaps slightly more specific, as they name things like character traits, personal thoughts and experiences, and gendered roles with which not all readers might identify.

For my kids, who always want to know what I’m writing, even when they know the answer will be so unsatisfactory as to involve neither dragons nor magical cats. Two Rogues Make a Right, Cat Sebastian

I grew up a PK (“preacher’s kid”). Emma, the heroine of this book, is a vicar’s daughter. I want to make clear that Emma’s father is nothing like my own. My father was – and is- loving, patient, supportive and understanding.

Thanks, Dad. This book’s for you. Please don’t read chapters 7, 9, 11, 17, 19, 21, or 28. The Duchess Deal, Tessa Dare.

This type of dedication is restrictive in its actual intended recipient, but contains jokes or other asides that give readers something to enjoy or interpret.

For Jess.

For FD.

For my mom.

The hardest kind of dedication to analyze is the one where the book is “for” a specific person, and I’m not going to cite actual examples. My reluctance to do so was telling for me: it felt weirdly interlope-y to cite specific personal dedications for the purpose of “close reading” them. I do not know (and I am fine not knowing) anything about my favorite authors’ relationship to their mom/cat/editor/best friend/favorite barista. Which isn’t to say personal dedications are superfluous: they must be deeply meaningful to the author and the person to whom the book is dedicated. This article rather poetically calls dedications a “private moment in a public object,” which is a lovely way to think about them. It also explains a bit why I find these dedications abstractly poignant, if resistant to analysis.

The thing is, of these different types of dedication – from the most general to the most restrictive – none of them change much of anything about a reader’s individual relationship to the text. All of them assume that some ineffable facet of the book belongs to the author and can be transferred to an individual or group, almost as a gift or offering. It’s a statement of intention and possession, one that might allow us to reframe books as having multiple modes and levels of belonging to different readers.

What do I mean by modes of belonging? I’m about to make obvious distinction, but bear with me. The front matter of books contains several kinds of written statements regarding, broadly, to whom the book belongs. One of the first pieces is a “Copyright [Author Name]” and an “All rights reserved” statement that clarifies a publisher’s right to restrict use of the book. At least part of their enforceability is predicated on those words being written: for fans of speech-act theory and the like, it is a statement that does something. A dedication, of course, is not a legal statement. It does not enforce a paradigm of ownership or transfer any rights to the recipient. The beloved cat to which the author dedicated a book cannot show up and argue that it’s theirs (though I would be very excited and they could definitely have my copy). While “Copyright [Author Name]” and “All right reserved” meaningfully and legally define the relationship of at least two different parties to the text, there is no observable difference in the relationship between me as a reader and a book that is dedicated “To the readers” or “To all the difficult heroines” or “To my mom.”

I’m belaboring an obvious distinction because of the way we sometimes talk about enjoyment of books as ownership or acceptance of a personal gift. To get insufferably granular, I want to tease out what we mean by the various “for”s in dedications, and how they can exist simultaneously. Books are “for readers” in the broadest sense possible, in that readers are the intended audience and purchasers of the product. Consumers also own any physical iteration of a book they’ve purchased (although Elizabeth Kolbert’s recent New Yorker essay persuasively argues that ebooks are redefining our entire notion of property rights.)

But the concept that we possess books, or receive them as gifts, doesn’t stop at the boundaries of the physical object. In a more esoteric sense, there are a lot of ways readers talk about themselves as designated recipients of book’s content, in ways that have nothing to do with authorial intention (and around here we love it when things have nothing to do with authorial intention). Saying that a novel “wasn’t for me” can be a way of acknowledging that a book was good but not to one’s personal tastes. Conversely, readers often describe loving a book as it having been written “just for them.” This kind of framing comes up if the book’s message is particularly resonant, or offers a recognition of one’s life, experiences, or identity that had otherwise been absent. That we frame emotional connection to a book as ownership or possession – a text that invisibly dedicates itself to the individual reader – is fascinating to me.

It also raises the question of what it means to lose possession of a book. Not the sense of losing your copy, but rather, when something happens that makes the book unreadable. Maybe with the benefit of age you discover that the book had problems you never saw before. Maybe you discover that the story builds itself by fictionalizing the very real pain of others in a way that, once seen, you can’t enjoy. Maybe the author turns out to hate people who are like you, or like the people you love, and employs their wealth and celebrity trying to make the world a worse place. Some people can separate the art from the artist, some can continue to enjoy the art as long as they cease financially supporting it. Still others might take a certain cathartic joy in a boycott or a purging of the books from their life. But a lot of readers just… lose those books. And then don’t know what to do with that loss.

In the first post of this series, I talked about how Gerard Genette conceived of paratexts as “thresholds,” or point-of-entry spaces that prepared the reader for the book. Having read through this front matter, it strikes me more as a set of bridges. There are bridges that allow us to enter the world of a book – with paratextual expectations fairly set – but there are also bridges through which the contents of a book enter our present time or our mental universe. We joke about fictional characters and moments “living rent-free” in our heads, and I’ve often extended that metaphor to imagine really great books showing up to my brain and rearranging the furniture. Like when a mundane object you’ve seen a million times in your life plays a central role in a novel, such that every time you see it you think about the book. That, too, is a kind of ownership, a way a book becomes for you even it wasn’t dedicated to you. So struggling with the loss of a book like that doesn’t, to me, suggest a maladaptive inability to “separate the art from the artist.” It’s just that one of the bridges between the book and the world around you is letting in pain instead of comfort, allowing it to rearrange the furniture in your brain in unwelcome ways.

Despite being the most opaque kind of paratext – a “private moment in a public object” – dedications let us imagine a different paradigm for receiving and possessing books. Regardless of what kind of dedication a book has, or whether it has one at all, there are meaningful ways in which any book you love is for you even while it’s also for someone else. This kind of ownership is deeply rooted yet frustratingly easy to lose, a tenuous possession both individual and shared. I don’t know that thinking about books this way makes it any easier to know what to do when you “lose” one. But it does make me all the more grateful for the ones I haven’t lost, and all the small strange ways they’re mine.

A fascinating essay– thanks! I have tried to keep the front matter brief in e-books to a)allow the reader to jump in and b) make sure the reader gets the meat of the book in an Amazon preview. But I think I might move my dedication up to the front and make a statement or two.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Paratexts, Part Three: The Art of the One-Click | Close Reading Romance

Pingback: June Wrap Up – firewhiskeyreader